The concept of project finance requires the sponsors to adopt a unique organizational structure in the form of a stand-alone project company (that is, a special purpose vehicle, SPV) which will enter into a PPP agreement with the government to design, build, and operate the project. This SPV has a finite life that equals the duration of the concession agreement. The sponsors are the only shareholders of the project company and their exposure is limited to the amount of equity investment that has been made in the project (with potential exceptions in some projects during the Construction Phase).

Because the SPV will not have any operating history, the lenders look primarily at the projected cash flows of the project as collateral instead of the project assets (which will not have much value in the case of financial distress). Lenders, therefore, require assurance that the project will be put into service on time, and that once the project is in operation it will be an economically viable undertaking. Similarly, in order to avail themselves of the funding, the project sponsors need to convince the lenders that the project is technically feasible and financially viable.

In assessing a project’s viability, lenders also examine the technical feasibility, financial feasibility and creditworthiness of the project (the capacity of the project to service the debt considering a certain degree of downside in the cash flows available) in order to decide whether to advance a loan or not (the due diligence process).

The technical feasibility of the project is examined to ascertain that: (1) the project can be constructed within the proposed schedule and within budget; (2) once completed, the project will be able to operate at the planned capacity; and (3) construction cost estimates, along with the contingencies for various scenarios, will prove adequate for the completion of the project. In evaluating the technical feasibility, it is necessary to take into account the influence of environmental factors on the construction of the proposed facilities and/or operation of the constructed facilities. When the technological processes and/or design envisaged for the project are either unproven or on a scale not tried before, there will be a need to verify the processes and optimize the design as part of evaluating the project’s technical feasibility.

From a broad perspective and general analysis, the financial viability (or commercial feasibility) of the project is assessed by determining whether the net present value (NPV) is positive. NPV will be positive if the expected present value of the free cash flow[1] is greater than the expected present value of the construction costs. However, in addition to or in lieu of the NPV, lenders will use debt ratios such as the Debt Service Cover Ratio (DSCR) and Life Loan Cover Ratio (LLCR) as the main ratios to measure bankability.

The DSCR measures the protection of each year’s debt service by comparing the free cash flow (more precisely, the cash flow available for debt service – CFADS) to the debt service requirement. The DSCR requires that the cash flow available for debt service is at least a specified ratio (for example, 1.2 times) of the scheduled debt service for the relevant year. The LLCR compares the overall amount of free cash flow projected for the life of the loan, duly discounted with the amount of debt under analysis. The LLCR also reflects the capacity of the SPV to meet the debt obligations over the life of the loan (considering potential re-structuring[2]).

On the basis of the projected cash flows of the SPV, including the debt profile under analysis, lenders and their due diligence advisors will observe the value of such ratios, and accommodate the debt amount so as to meet them, considering the maximum term at which they are ready to lend. Subsequently, they will run sensitivities analysis (including break-even analysis) on the project cash flows to test the resistance of the project to adverse conditions or adverse movements of the free cash flow figures from the base case.

In determining financial viability, and related to the reliability of cash flows and the guarantees offered by the contract (especially termination provisions), the lenders will analyze the risk structure of the contract. This will include determining how achievable the performance standards in government-pays projects, or the contractual guarantees in user-pays projects, actually are.

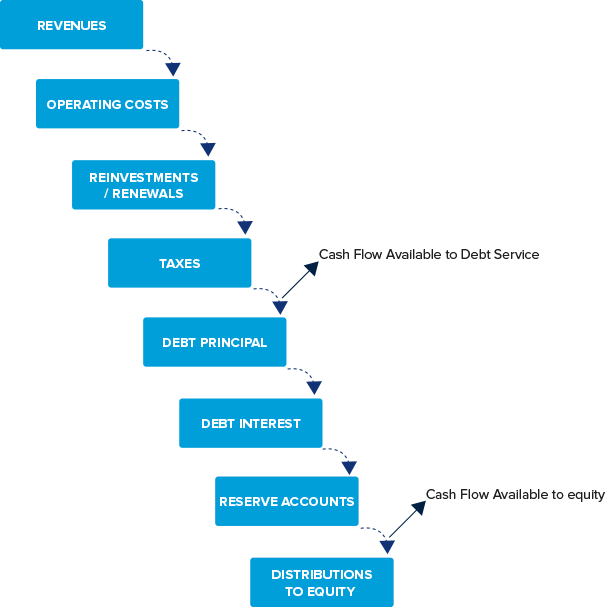

Lenders will exercise tight control of all cash flows, limiting the ability of the private partner to dispose of them — through “covenants” (for example, no distributions may be made if the actual DSCR of the previous year has not meet a certain threshold). The bank accounts through which cash flows pass will be pledged and held with a bank within the syndicate; this is in addition to other provisions to be adapted in the loan agreement[3]. Cash flow payments will be subject to prioritization rules defined in the loan agreement under a “waterfall” sequence (see figure A1 ).

FIGURE A1: Waterfall of the Project Cash Flow Payments

[1] Free cash flow is what is left over after the company has paid all the costs of production (operating and ordinary maintenance costs) and taxes, and has made any capital expenditures required to keep its production facilities in good working condition.

[2] The Project Life Cover Ratio (PLCR) is often used as a secondary measure. It compares the cash flow of the entire project life against the debt amount.

[3] Appendix A to chapter 6 discusses further typical conditions and covenants which are usually incorporated in a project finance loan.

Add a comment