2.1. Importance of Contract Management and Monitoring

The previous chapter (sections 3 and 4) explained the importance of: the contract management and monitoring; providing for the governance, structure and function of contract management; and the contract management team. The principles of the governance, structure, and function remain the same throughout the Operations Phase. However, during the Operations Phase, key actions for the contract monitoring team change, covering areas such as managing payment regimes, including insurance and utilities, acting on the results of customer surveys, looking for continuous improvement in the service, and performance monitoring.

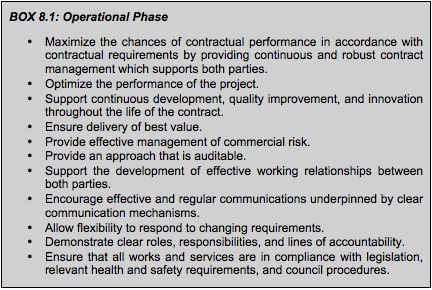

Sound contract management throughout the operational phase will have the following  traits listed in box 8.3.

traits listed in box 8.3.

2.2. Reasons behind Unsuccessful PPP Projects during the Operations Phase

Failure to implement an adequate contract management system could result in the following outcomes.

The government paying for services which are not being received or are not being performed satisfactorily.

Any lack of government involvement and monitoring of private party delivery could lead to a sense of complacency by the private partner; this can lead to the delivery of sub-standard services while government payments or user fees continue to be paid. This can occur in those accommodation projects in which facilities management plays a big role in the Operations Phase and the public party is not closely linked to the users of the facilities.

The project not performing as anticipated, thus jeopardizing project benefits.

In many cases, particularly in transport sector projects where user payments are crucial for realizing project benefits, possible failure points exist where high user charges and/or poor service or asset standards deter users and diminish project returns. This is the highest risk where the government has assumed some demand risk through, for example, minimum revenue guarantees.

Changes to the balance of risk negotiated in the contract.

Sometimes the government, through inappropriate involvement in various stages of the PPP lifecycle, can reverse the risk transfer and assume risks allocated to the private party. Usually, this happens due to lack of knowledge by the public officials. For example, if the procuring authority implements its own minor modifications during the Operational Phase outside of the contractual modification process, it may take back risk associated with the life-cycle costs and the condition of relevant parts of the facility.

The government is unable to foresee operations and management (O&M) contractor failure or put in place contingency measures.

At the time of the signing of the PPP contract, the future cannot be told with certainty. The procuring authority should be vigilant in monitoring the financial and performance aspects of the O&M contractor over the whole Operations Phase. Events such as solvency of the O&M contractor, or changes in the ownership or business direction of the contractor, could hamper the success of the PPP and cause major failure.

A breakdown in relationship with the O&M contractor

As in any relationship, collaboration and understanding are fundamental to a successful PPP. Simple issues such as contract misunderstandings, failures to gain stakeholder buy-in, and abusing certain situations can lead to a breakdown of the relationship and failure of the PPP.

Table 8.1 analyzes a selection of projects that cancelled during the Operations Phase.

|

TABLE 8.1: Projects Cancelled during the Operations Phase |

||

|

Project |

Reason |

Reference |

|

London Underground PPP (UK) |

The responsibility of infrastructure maintenance and rehabilitation of the London Underground system was given to the private sector, and it received annual grants from the government. The PPP arrangement was for a period of 20 years, beginning in 2004. Yet by early 2010, the control of infrastructure was returned to the government. This research highlights the reason the project was cancelled as problems in consortium management, a lack of government control, incompleteness of control, and a lack of appropriate risk transfer. |

Analysis London Underground PPP Failure

|

|

Victoria Trams and Trains (Australia) |

The government awarded a series of franchises for Victoria’s trams and trains to the private sector for operation and maintenance, in which demand risks were primarily borne by the private parties. Demand turned out to be lower than expected, resulting in financial difficulties for the companies. However, the government’s risk monitor was unable to identify the deteriorating financial performance. The private parties had to walk away from the contract, leading to renegotiations on the government’s part. |

Avoiding Customer and Taxpayer Bailouts in PPP projects wps3274bailouts.pdf

|

|

Water Services for Metro Manila (Philippines) |

The Manila Water Supply System was privatized in 1995, and Maynilad Water Services (MWSI) won a 25-year concession to operate the services for the west area, while the Manila Water Company (MWCI) was successful for the east area. However, due to the Southeast Asian economic crisis, the cumulative debts in the Philippine peso swelled by 60 percent. The MWSI was obliged to raise the tariffs. Later, the government declared a freeze on water tariff hikes. In response, MWSI revoked its operation rights on grounds of breach of contractual terms for tariff revisions. |

|

|

Dar es Salaam Water Distribution Project – DAWASA (Tanzania)

|

The project was awarded to City Water for billing, collecting revenues from customers, making new connections, and performing routine maintenance. However, the contract was terminated within two years of operation, followed by complex arbitrations between the government of Tanzania and City Water. City Water was found to be highly inconsistent in its operations. The project had suffered from weak risk mitigation measures, inefficient contract monitoring, and improper bidding procedures. |

|

Add a comment