Variation management is closely connected with PPP agreement management and relates to the creation of mechanisms to enable changes to the PPP agreement. Such changes may be necessary as a result of a change in circumstances that could not be anticipated or quantified when the PPP agreement was signed. Variations may involve changes to works, services or the form of delivery.

The four main categories of variation types include:

- Variations that involve no additional costs;

- Small works variations;

- Government variations; and

- Private party variations.

There are procedures for all of these categories, which must be applied in cases of changes to the PPP agreement regarding works, services, and the means of delivery. Given the length and complexity of PPP agreements, it is likely that these procedures will be invoked from time to time to deal with changing project needs.

Variation procedures must be used effectively to ensure that other important functions, such as performance management and risk management, continue to operate in line with contractual requirements and changing service delivery imperatives. The contract management team must become familiar with all of the intricacies of each variation procedure and ensure that the correct steps are followed whenever the need for change arises.

7.1. Variations that Involve No Additional Cost

In circumstances where a proposed variation involves no additional costs for either party, no formal variation procedure is required. The procuring authority and the private partner should meet to discuss the best way of implementing the proposed change. If the variation will result in a reduction in costs, then the two parties will need to reach agreement about how to distribute such savings. In the case of a variation proposed by the procuring authority, savings should accrue to the procuring authority and/or end users, while savings derived from a variation proposed by the private partner should be divided between the procuring authority, the private party, and end users. The two parties would be expected to reach agreement on implementing this category of variation without recourse to dispute resolution procedures.

7.2. Changes in Small Works

Some PPP contracts include a small works variations procedure, designed to provide an efficient mechanism for dealing with minor additional capital works required by the government. For example, the PPP agreement can require the private partner to provide a schedule of rates for a range of likely small works at the beginning of each year.

Any dispute between the parties relating to small works variations must be determined in accordance with the dispute resolution procedures.

7.3. Managing Government-Initiated Variations

Government variations should be limited to changes to the services requirements, the specified constraints on inputs, and the limits or scope of the project insurances. If the government wishes to make a change to the project deliverables, it must first submit a variation proposal to the private partner. The variation proposal must describe the nature of the variation and require the private partner to provide an assessment of the technical, financial, contractual, and timetable implications of the proposed change within a specified period.

After meeting with the private partner to consider its response, the government must decide whether it or the private partner should finance the variation. Depending on who provides the funding, payment for the variation should be made by any necessary adjustments to the user fees or unitary payment (if the private partner is financing the variation) or other forms of payment. Disputes between the parties relating to a variation (which does not involve a decrease in the scope of the service or adversely affect the private partner’s risk profile) must be resolved in accordance with the dispute resolution procedure.

In situations where the government’s requirements for variations can be foreseen to a reasonable degree before the signing of the PPP agreement, the government should explore the feasibility of requiring the private partner to commit to pricing pre-specified variations as part of the PPP agreement. This would provide for an accelerated variation procedure after the PPP agreement has been signed.

7.4. Managing Private Partner-Initiated Changes

If the private partner wishes to introduce a variation, it must submit a private partner variation proposal to the procuring authority, setting out the details of the variation and the likely impact thereof on the PPP agreement — particularly in relation to unitary charge payments. After meeting with the private partner and providing it with an opportunity to modify its variation proposal if necessary, the procuring authority must decide whether to accept it.

Generally private partner-initiated changes should be at no cost to the government or end-users, although there may be cases where the change is beneficial to both parties and the government is willing to contribute to the cost or increase the user fees. If the procuring authority decides to accept the proposal, it will need to make any necessary arrangements for payment depending on the funding regime that has been agreed.

7.5. Managing Interfaces and Required Changes

Although PPP contracts allow flexibility for changes in the physical infrastructure or the services, this flexibility is only effective if the government appropriately manages the variation process. Foster Infrastructure (2012)[11] states the following key principles that are applicable to managing variations.

- Understand the contract: The government’s contract management team should ensure that they understand the PPP contract. This is essential not only to ensure that rights and obligations in relation to variations are being honored, but also to verify that a variation request is actually a change and not covered under the existing agreement and pricing structures;

- Adopt a strategic approach to variations: The government should adopt a strategic approach to variations. It should control the flow of variations to avoid overstretching resources on either the government side or private partner side of the contract. For example, the government can consider bundling similar variations together to reduce costs, or plan a variation program based on anticipated needs;

- Ensure variation requests are clear and comprehensive: The government should provide its private sector partners with proper briefs to make it clear what it wants done. This is especially important for larger, more complex variations. For complex variations, the government should consider initially having informal non-binding discussions with the private partner in order to better understand its ability to implement the variation prior to issuing a formal variation request. These informal discussions can enable the government to prepare a formal variation request that gives the private partner the information it needs to enable it to fully evaluate the variation and provide a detailed implementation plan;

- Establish clear and appropriate roles and responsibilities for requesting and assessing variations: The government should ensure that the appropriate staff has the authority to request and authorize variations, and that the staff without the authority to request variations understand this. Potential variations should be assessed thoroughly by suitably experienced personnel who should consult with relevant stakeholders; and

- Maintain good record-keeping practices: The government should keep good records of the variations and payments made, and it needs to ensure that agreed variations are clearly documented with the private partner. It should ensure that robust methods for costing are demonstrated by the private party for all variations (such as benchmarking and market testing), and that they have signed up to the governmental procedures when providing quotes for works of any significance. The government should further challenge information provided by the private party to ensure it is satisfied with the ability of the partner and also to demonstrate that they are achieving best value. The government should also ensure that they have a register in place through which to record all variations to the service. This will enable it to manage budgets, and understand any changes to cost provided during benchmarking and market testing. It will also provide an audit trail of variations to the contract.

7.6. Benchmarking and Market Testing

The aim of benchmarking and market testing is to ensure that best value and service performance is maintained for services during the Operations Phase. This is done by adjusting the government payments to reflect the current cost of providing services (see section 4.10.10 of chapter 5 for further discussion of payment adjustments). If a decision is made to use benchmarking or market testing[12], appropriate provisions should be drafted into the contract. It is important to ensure that these exercises are carried out in accordance with the contract, and that the agreed drafting properly reflects the needs of the service/project.

The government is used to performing benchmarking for services, and many have such a procedure in place. The contract may include an obligation for services to be benchmarked and/or market tested at intervals, and defined in the contract during the operational period. Both benchmarking and market testing should be implemented to demonstrate long-term best value of service provision in PPP contracts. This is commonly referred to as “value-testing”.

In PPP contracts there is a requirement for the private partner to manage these value-testing processes and bear the cost of running the process. However, the private partner and the government should carry out the benchmarking and/or market testing as a joint exercise, as there would be little value in the private partner performing the exercise and simply reporting the results as they both must agree on a Value for Money outcome. Therefore, the main focus of this exercise should be on the private partner demonstrating Value for Money and the government using value testing as a means of securing the best deal. Value testing is an ideal opportunity to review the output specification and to adjust service levels to better meet the authority’s requirements for the future, subject to cost implications.

Similar PPP projects (in size, complexity, and service level) should be benchmarked against other standard benchmark data. Good practice is to establish a project team comprising representatives from the private partner and the government to oversee the benchmarking exercise. Practical arrangements for this should be drawn up in conjunction with the private partner well in advance of the actual benchmarking and market testing.

The contract will set out the timing of the benchmarking or market testing process. Typically it is conducted every 5 to 8 years. Governments that have gone through such exercises suggest that from initial discussions to final agreement, benchmarking may take a minimum of nine months. If it is followed by market testing, or if market testing alone is conducted, the process could take up to two years. The government therefore needs to employ project management disciplines from the outset and produce a project plan to cover the following considerations.

- Reassessment of requirements and possible changes to the specification;

- The schedule including agreement on milestones;

- Definition of respective roles including agreement around responsibilities;

- Methodology including agreement with regard to the approach to be employed; and

- Communications through which everyone remains informed.

A clear plan, agreed from the outset, that has a timetable allowing adequate time for iteration, clarification, and negotiation, is required. Procuring agencies should be involved early in the process, and all relevant legislation and appropriate guidance relating to employee rights must be fully complied with.

Specialist technical, financial, and legal advice may be required by the government, and it should be noted that benchmarking and market testing can be a resource intensive activity. The government needs to plan its budgets carefully for these exercises.

Both parties should independently collect data to be utilized for comparative purposes in the value-testing exercise. The private partner will utilize their data to identify a benchmark cost for the services, and the government will utilize their data to examine, interrogate, and validate the results of the exercise. Comparative data should be valid and is required to be transparently compiled. The private partner’s own costs of providing services are not a valid comparator. The data compiled will need to be adjusted to be project specific, taking specific aspects of service provision and factors, such as regional variations, into account.

Openness and fair competition are key aspects of any market testing activity. As such, a government needs to encourage an active bidding market while avoiding potential conflicts of interest between the private partner and its bidding sub-contractors.

7.7. Changes in Ownership

During this phase, changes in ownership may occur, as can be the case during construction. In some jurisdictions, changes in ownership during the Operations Phase may be subject to fewer limitations than those during construction. Refer to chapter 7.8.2. for a description of this change event and its management issues.

7.8. Refinancing

The EPEC PPP Guide defines refinancing as one of or a combination of the following:

- A reduction in the debt pricing;

- Extension of the debt maturity;

- An increase in the gearing (that is, the amount of debt relative to equity). This is possible when lenders are prepared to relinquish some of their contractual protection as the perceived project risks are reduced;

- Lighter reserve account requirements; and

- The release of guarantees provided by the shareholders, sponsors or third parties of the private partner.

The underlying commercial rationale is that, by restructuring its financing arrangements, a private partner is able to raise more debt for the same debt service amount. This typically reflects the fact that, once a project has successfully reached its Operations Phase, the risks for lenders are lower and banks will accept a lower interest rate. The financial benefits derived from this additional debt and/or cheaper debt then becomes a refinancing gain that, under some PPP contracts, is shared between the private partner and the government. Where taken by the private partner, the refinancing gain is in the form of increased or accelerated distributions to the equity investors, for example. In this case, they are paid out as an extraordinary dividend or an early prepayment of shareholder loans at the time of refinancing.

Where the government receives a share of the refinancing gain, this is typically as a once-off capital amount paid by the private partner or, in the case of a government-pays PPP, possibly as a decreased unitary charge payment over time. In a few rare cases, the benefit is taken “in kind” as a pre-funded variation financed with the government’s refinancing gain share. This is rare because of the difficulty in estimating the value of the variation at the time of entering into the PPP contract.

7.8.1. Benefits of Refinancing

Refinancing gains can be significant for large infrastructure PPPs. The benefits of refinancing contract clauses are as follows.

- The private partner is incentivized to perform well under the PPP contract so as to increase the confidence of refinancing investors and to maximize the refinancing gain.

- The government is also incentivized by the prospect of a refinancing gain share to cooperate with the private partner, and to deal with potential risks to the PPP that are in its control, as well as potential increased risks not under its control.

- A refinancing can make the financing much more efficient and transfer value that would otherwise have gone to lenders, project sponsors, users, and taxpayers.

7.8.2. Risks of Refinancing

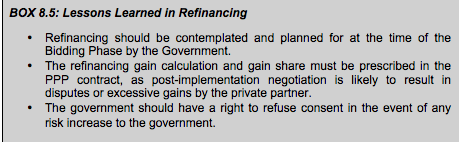

While refinancing gains can be large, they are often forgotten about in developing PPP markets because the emphasis is on reaching the implementation stages of the project. As experienced in more developed PPP markets, refinancing does come with some risks.

- A refinancing that incurs additional debt may also increase the contingent liability of the government in an event of private partner default if a percentage of the outstanding debt has been guaranteed by the government;

- Refinancing that involves re-gearing of the debt equity ratio may change the risk profile for the project. This may reduce the equity sponsors’ incentive to stay in the project and see it through difficult times after the refinancing;

- Refinancing gain shares that inappropriately understate the risk taken by the government or overstate the efficiency of the private partner lead to negative public perceptions about PPPs, and therefore a gain sharing that cannot be justified as being in the public interest; and

- In some countries, refinancing has become a highly regulated activity with regulatory approvals and prescribed methods of calculating the refinancing gain share[13].

There are three fundamental issues that have to be determined in a refinancing.

- What approval rights should the government have in a refinancing?

- How is the refinancing gain calculated?

- How is the refinancing gain shared?

There is, unfortunately, no simple answer to each of these questions. Each PPP jurisdiction will have different economic and market conditions from the other, and each project will have different risk profiles. Although an oversimplification of the factors to be considered, the risks assumed by the private partner must be the foremost consideration of the government in establishing the refinancing gain share mechanism for the PPP contract in the bidding stage.

For user-pays PPPs where the private partner takes full demand and revenue risk (and in some jurisdictions there is no compensation on termination for private partner default), there will be a strong argument for a refinancing gain share to be heavily slanted in favor of the private partner. However, the economic factors that may increase the financing gain are seldom in the control of the private partner (for example, low interest rates as a result of a national or regional central bank policy), and yet these factors are material to the success of the refinancing.

In UK, for example, a refinancing market has matured since the beginning of PFI. It went from 70 percent of the refinancing gain to the private partner before the standardization of PFI contracts in 2002 to a 50 percent gain share with prescribed methods of calculation in Standardisation of PFI Contracts (SoPC) post 2002. More recently, the amendments to SoPC4 in April 2012 state that the government is entitled (in the event of a reduction in the margin of the debt to be refinanced) to a 90 percent share of the portion of the refinancing gain arising from the decreased margin.

Similarly, in South Africa, the refinancing gain share of the government was set at 50/50 after 2004 when the National Treasury introduced the Standardized PPP Provisions. Prior to this, there was no refinancing gain share prescribed for South African PPPs. See box 8.5 for lessons learned from refinancing.

7.8.3. Calculating Refinancing Gains

Refinancing gains are generally calculated by comparing the distributions that are payable with refinancing to those without refinancing. Distributions generally take the form of dividends paid to shareholders or repayments of shareholder loans. As such, the gain is not simply the amount of additional finance raised, but rather the calculation is an artificial construct calculated from the perspective of the equity provider and based on the extent to which the refinancing provides a return above the base case return.

The refinancing gain is normally calculated as a net present value of the projected equity cash flows using a discount rate that reflects the nominal, post-tax internal rate of return (IRR) of shareholder equity used in the base case financial model.

As the South African Standardized PPP Provisions points out in paragraph 80.2.1, changes in the distributions forecast to take place after the refinancing can be negative and positive. For example, if the private partner raises additional amounts of debt that is paid out as an immediate distribution, this will be an increase compared to the pre-refinancing position, while the debt service payments after the raising of the additional debt will be greater and future distributions lower than the pre-refinancing position.

It is a complex set of assumptions and scenarios, and the government is advised to prepare well with financial and legal advisors prior to any refinancing.

Many details (for example, the discount and interest rates to be used in the calculations, treatment of the possible impact of a refinancing on the termination payment that the government might have to make in the future) need to be addressed in the PPP contract to avoid subsequent negotiation and possible disputes. As with many other aspects of PPPs, it is important to anticipate the issues as much as possible and set out detailed provisions in the PPP contract.

7.8.4. Payment of Refinancing (approvals required)

It is a recommended practice that the government and the government entity in control of contingent liability and fiscal risk management provide separate approvals before the refinancing occurs. The obtaining of such approvals as early as possible in the process also assists the private partner in its engagement with potential refinancers because the support of the government will be considered as a strong positive by the market.

The government should ask itself the following questions when considering its approvals.

- How much is its likely refinancing gain share?

- How much additional debt will be incurred by the private party?

- What is the change in risks for the project and the government?

- What is the risk of termination of the project and what is the net increase in any contingent liability?

- What is the impact on the private partner’s ability or capacity to manage and mitigate the risks under the PPP contract?

- What are the incentives for the private partner to maintain service standards after the refinancing?

- Will the refinancing undermine the financial stability of the private partner?

After obtaining quantified answers to these questions from expert advisors, the government should objectively assess the private partners’ proposals. If so justified, the government may, for good reasons, refuse to approve a refinancing despite the opportunity to share in the refinancing gains.

This right to approve a refinancing does not extend to cases where the refinancing takes place in the regular execution of the PPP contract or the loan contracts. These include cases where the refinancing:

- Is a sale or cession of the whole or any part of equity or the shareholder loans or;

- Was taken account of fully in the base case financial model and approved as such or;

- Arises solely from a change in taxation or accounting treatment;

- Occurs in the ordinary day-to-day administration of the loan contracts;

- Affects any syndication, sell-down, cession or grant of any rights of participation or security held by the lenders.

[11] Foster Infrastructure (2012), Comparative Study of Contractual Clauses for the Smooth Adjustment of Physical Infrastructure and Services through the Lifecycle of a PPP Project, Foster Infrastructure Pty Ltd.

[12] Market testing and benchmarking are the two most common approaches to “value-testing”. Contract management (and the contract) may apply only one of the two approaches, or may allow both. To learn more about each of these procedures, refer to Standardization of PFI2 contracts (HMT, 2012), Schedule 2 in page 366. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/fil...

[13] United Kingdom Treasury (2007), Standardisation of PFI Contracts Version 4, http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/ppp_standardised_contracts.htm [accessed: 02 March 2015].

Add a comment