The structure of the contents of the contract document may vary significantly from country to country, and even depending on the authority or level of government within the same country. It is preferable that the structure of the contents, the nomenclature, and the treatment of many commercial matters are the same or similar (always respecting the specific characteristics of each project and sector) within one particular market, with the incorporation of contract guidelines or standards (see box 5.29 ) to the PPP framework.

|

BOX 5.29: Use of “Standard Contracts” and “Contract Models” Chapter 2 (box 2.8) explains issues associated with the development of standard contracts and contract models as part of a PPP framework. When drafting the contract for a specific PPP, standard contract provisions and contract models should be used with caution, unless their use is mandatory and cannot be departed from in the context of the specific project. This is because, generally, they are intended to be global, so they are not tailor-made to specific markets or projects. Certain and very specific clauses should, however, be standardized as long as it is clear that they appropriately reflect the government’s strategic approach to a specific issue regardless of the project specifics (for example, the language for contract termination). However, a formal standard contract (that is, mandatory) should only be developed when a high degree of experience has been developed through precedents. When standard contracts or standard clauses are provided in the form of examples from other regions or countries, these can be a valuable resource. However, they may need to be adapted to a different PPP jurisdiction and, most likely, to the specific project. |

Therefore, there is no universally valid recommendation regarding the structure of the contents of a PPP contract. For some countries (civil law countries), it is even usual that certain provisions (for example, the termination of contract) are regulated extensively in the law. This PPP Guide considers it good practice to also develop such provisions in the contract so as to adapt them to the extent permitted by the law to match the project specifics, and for greater clarity and transparency (especially for international investors).

This PPP Guide also considers that legal frameworks (issuance of framework documents reflecting the law) are good, but they should provide general principles and leave space for the contract to fine tune risks and other contract structure matters.

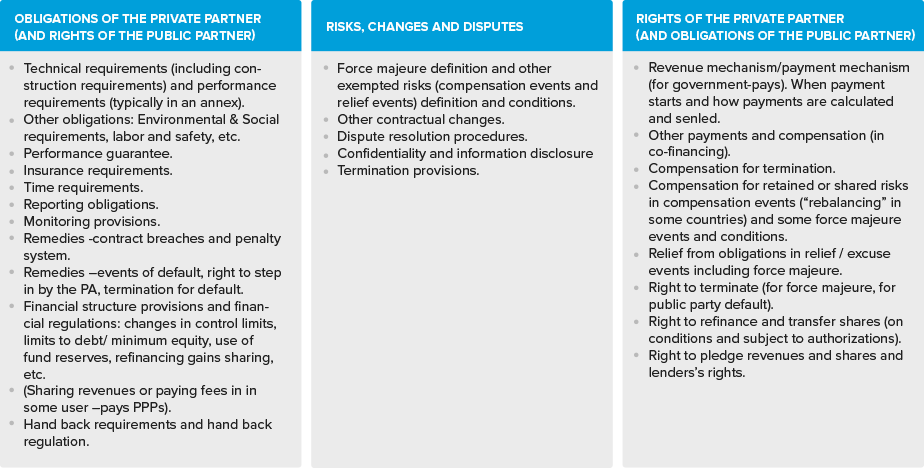

Figure 5.12 lists the main kinds of provisions within a contract, grouping them in three categories in order to facilitate a clearer understanding, but recognizing that the complexity of a contract requires a richer and more multifaceted structure in terms of chapters or titles.

Above all, a contract governs the obligations and rights of the parties. Everything starts from a clear definition of the scope of the contract and the responsibilities of the private partner for the full contract cycle. This includes prescriptions and descriptions of output targets (design, construction and financing, commissioning, operate and maintain, hand-back) followed by the private partner’s economic rights (the right to receive payment for the work done). This latter provision implies that the main obligation of the public partner (that is, to pay required amounts when due) reaches its maximum complexity when dealing with government-pays payment mechanisms.

PPP contracts are also about the delegation of the delivery and management of a public good (public works) and/or service. Therefore, the public party’s rights of oversight and control, and tools or means to monitor and remedy lack of performance are essential contents of the contract. These include the definition of breaches and the related penalties or LDs, the process for any deductions from service payments, the rights of the public party to step in, the right to inspect, and the obligations on the private party to report, and so on.

Finally, the contract must govern changes and risks affecting the successful outcome of the project. For this purpose, the contract will foresee and prescribe the framework for allowed changes in the scope of services and obligations, and changes due to certain risk events occurring (see risk structure section). This latter feature of the contract, together with the right to monitor and handle performance problems, is the main framework for contract management[83] (which is extensively covered in chapters 7 and 8).

FIGURE 5.12: Main Provisions in a PPP Contract

Technical requirements (section 3.3), financial structure matters (section 4) including the payment mechanism, and risk-related provisions (section 5) have already been explained in some detail.

This section provides some details and recommendations on a number of additional aspects and provisions with significant commercial relevance.

- Performance requirements and performance management issues and provisions;

- Contract breaches, penalty system, and default events;

- Compensation events and rebalancing regulations;

- Other financially-related provisions: financial structure (minimum equity/maximum leverage), changes in financing (refinancing) and ownership, insurance requirements and performance guarantees, and lender´s rights;

- Intellectual property and confidentiality;

- Contract changes;

- Dispute resolution matters;

- Early termination provisions; and

- Hand-back provisions.

[83] See Management PPPs during their Contract Life (EPEC, 2008) page23 – The PPP Contract: The Main Operational Management Tool. http://www.eib.org/epec/resources/epec_managing_ppp_during_their_contrac...

Add a comment