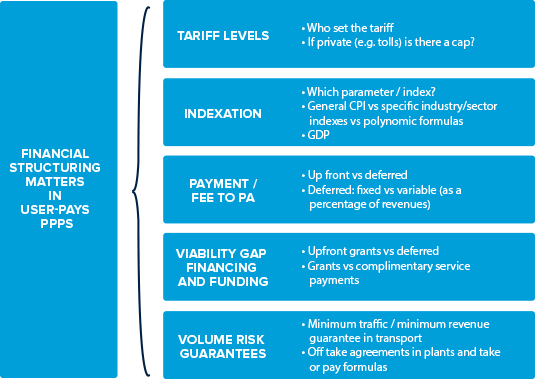

As introduced in chapter 4, when the private partner’s revenue is based on user-payments, there are a number of structuring parameters that should be carefully considered and outlined during appraisal. These should then be refined (and in exceptional cases reconsidered) in the Structuring Phase. See figure 5.6.

- Definition of toll/tariff levels. In road projects subject to tolling, the government typically sets maximum toll levels (per type of vehicle) and other general parameters for the toll structure. In some projects, a maximum average tariff is defined, giving some flexibility to the private partner to apply different toll strategies subject to general caps within the basic tariff structure. Higher flexibility is seen in some projects, especially those with dynamic tolling[18]. The basic strategy (that is, the extent to which flexibility will be granted to the private party in defining toll levels) and the basic structure of tolls (especially defining caps) is usually determined in the Appraisal Phase, but marginal changes might be made during Structuring Phase.

In water projects related to the integrated water cycle (that is, including infrastructure provision, water supply to homes, and tariff collection), the tariff is always regulated because of its nature as a basic ‘public good’ and there is usually no room for tariff definition by the private partner. This is also commonly the case in public transport projects.

- Tariff revision or indexation. When tariffs are capped, they will usually be reviewed (yearly in arrears) and indexed during the term of the contract. While a basket of indexes may be used, the most common approach is to index the tariffs to a general inflation index (usually known as the Consumer Price Index, or CPI), while in some countries (for example, in Spain), a correction factor is included to incentivize higher efficiency in cost management (for example, tariffs are indexed at 0.85 x CPI). In some sectors with independent regulators, there are periodic tariff reviews (mostly for consumer tariffs) that take a wide range of factors into account. For example, in power generation, it is common to include an automatic pass through of fuel costs in the tariff, with monthly, 6-monthly, or annual adjustments.

Some schemes in road projects provide for flexibility in the indexation of the tariffs, allowing for linking the indexation to gross domestic product (GDP), or whichever is higher between GDP and inflation.

- Payments to the procuring authority (in projects expected to have excess revenues). When the project shows revenue potential in excess of that required for commercial feasibility, governments may opt to decrease the tariffs and pass that benefit thorough to the final users, or to capture that benefit as a financial revenue for the government (or a combination of the two).

The most typical routes for sharing the excess revenue are:

- upfront payments (also called an upfront “concession fee”); and

- sharing mechanisms during operations which may, in turn, be in the form of a fixed yearly payment or in the form of a variable payment (defined in terms of a percentage of the revenue earned)[19].

Sharing the potential “excess revenue” by shortening the contract term should be carefully considered as this approach to sharing gains will likely affect VfM and financial optimization.

An upfront fee should only be considered when there is clear evidence of the value of the excess revenue to the project company. The cost of capital matters should be considered, as the project company will have to raise additional capital in order to pay the fee. Concession fees should not be required at the cost of overcharging users with a higher than economically reasonable fee.

When the government decides to request an upfront fee (or needs to do so for fiscal reasons), it may be preferable to estimate a prudent value for the concession fee (that is, based on realistic and close to pessimistic traffic and revenue assumptions). The government may also capture the rest of the excess value or a part of it through a variable fee during the life of the contract.

Excess revenue most often arises in existing projects, that is, in existing infrastructure (usually roads[20], airports, and some ports), for which there is an established and known level of current use. Potential excess revenue can also be identified for some greenfield projects (mainly roads), although this is less common.

- Unfeasible projects. Conversely, there will be projects that are not financially feasible on the sole basis of user fee collection (not feasible on a stand-alone basis). This will have been identified in appraisal and the basics of the strategy to fill the gap will have been established, subject to a refinement in terms of financial structure.

- If a co-financing approach has been selected, the shape and form (especially the timing) of the grant payments will be defined at this stage to the extent it was not done previously.

- When feasibility is supported by participative soft loans (subordinated debt provided by the procuring authority), the terms of such loans will be determined now, although basic conditions should have already been settled during appraisal.

In these cases it is customary to include some mechanism to share potential upsides. This and others means to support feasibility of a project have already been explained in the previous section.

- Risk structuring matters related to volume. When demand risk is perceived as significant (for example, in a greenfield project for which there is no historical data that can be used to estimate demand), it may be necessary to limit or share such risk. This can be done through such contractual mechanisms as guarantees of minimum traffic/revenue or other similar mechanisms (see box 5.11).

FIGURE 5.6: Key Factors in Financial Structuring of User-Pays Projects.

Note: CPI= consumer price index; GDP= gross domestic product; PA = procuring authority.

BOX 5.11: User-Pays Road PPPs: An Example of a Revenue Shortfall Mechanism[21]

|

The 157-kilometer (km) tolled motorway M5 (Hungary) forms part of the Pan-European Transport Corridor IV (Berlin-Prague-Bratislava – Budapest-Thessaloniki-Istanbul). It was developed as a user-pays PPP (concession) in 1994 with a contract length of 35 years. The contract includes a “revenue shortfall mechanism” to make up for revenue shortfalls due to traffic during the first 7.5 years of operations (a mechanism that was in fact used to a limited extent). This provision contributed to the project being financially sustainable. However, the previous and the first road PPP in Hungary (the M1-M15 Motorway) defaulted and had to be rescued by the government. The mechanism is a revolving type: the contributions by the government to meet revenue shortfalls are construed as a subordinated loan that will be repaid on the basis of future benefits, with priority over the dividends to the private partner. The project also benefited from the participation of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) under an A/B loan structure. It included the right to review toll levels by the private partner on the basis of changes in currency exchange rates, and it was confirmed as a model for future projects in Hungary and the region. |

[18] Dynamic tolling or dynamic pricing refers to tolling levels that may vary in real time in order to respond to congestion. It is related to facilities in which there is a toll-free alternative so that drivers have the ability to use tolled or non-tolled options, depending on the level of traffic and the price. These projects are sometimes referred to as “express lanes”.

[19] A variation of this approach is to apply the percentage to be shared to the net profit or the Earnings before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization (EBIDTA) of the project company. This has the disadvantage of being more complicated to calculate and may more easily result in disputes. Another more complex approach is to base the sharing of excess revenues or excess profit in the equity returns (equity IRR) levels so as to share revenues or make payments to the procuring authority when the equity IRR exceeds certain thresholds.

[20] Box 1.10 in chapter 1 explains “Long term leases or concessions of an existing user-pays infrastructure as a special case of management or service PPPs with significant private finance”, including an example of a relevant project, the Chicago Skyway.

[21] Resource Book on PPP Case Studies (European Commission 2004) case study 19.

Add a comment