The basic form of the payment mechanism is defined during appraisal, whether the project is a user-pays PPP that relies on significant service payments to complement the revenue, or the project is a pure government-pays PPP where the operational revenue is entirely in the form of public payments.

If the payment mechanism provides for the government to make shadow payments based on volume (for example, shadow tolls, shadow fare payments in public transport, or payments per cubic meter in water treatment projects), this will introduce demand or volume risk to the risk structure. This risk is generally difficult for either party to control or manage, and lenders are wary of it — unless, that is, the nature and context of the infrastructure or service make the risk reasonably predictable (for example, with regard to demand in a road corridor with a long track record and an absence of competing roads now or in the future).

Volume risk structures should only be considered when there is a clear alignment of interests (that is, the public party is interested in higher demand or higher volume, for example, in urban public transport) and when the traffic or volume risk is considered to be reasonably assessable and manageable by the private partner. There may be cases in which the public party is interested in higher volumes, but there is no rationale for transferring volume risk. One relevant case is that of some rail corridors where the private partner is responsible for the Design-Build-Finance-Maintain (DBFM) of the infrastructure of the line, but the line itself will be operated by an incumbent operator or by other private operators. In this context, it is irrational to pay the private partner on the basis of traffic (the number of trains that use the infrastructure) as the volume is under the control and management of a third party. See also table 5.2.

|

TABLE 5.2: Examples of Improper and Proper Volume Risk Transfer in Government-Pays PPPs |

|

|

Improper Volume Risk Transfer |

Proper Volume Risk Transfer |

|

|

|

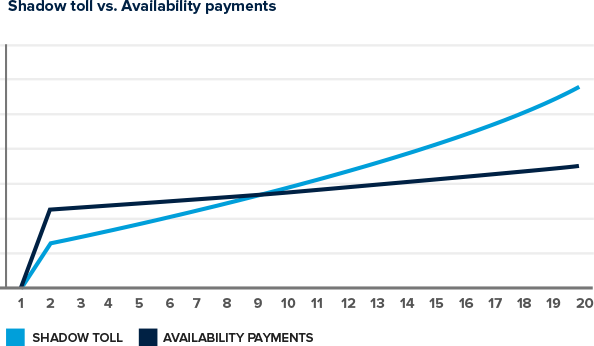

Volume payments (in transport) give the public party a theoretical advantage as they provide payments that increase over time in real terms because the long-term demand is expected to grow at a pace approximating the growth in GDP. Therefore, the payments can be back loaded (that is, lower in the early years of the PPP and higher in the later years). However, this has the inherent disadvantage of increasing the overall financial burden of the PPP scheme because the average life of the financing is longer, and it is likely that the DSCR required by lenders and equity IRR requested by the investor will be correspondingly higher. See figure 5.7.

|

FIGURE 5.7: Payment Profile in a Road PPP: Volume versus Availability

When a shadow payment is used, the payment profile will be affected by the evolution of traffic demand which usually increases over time (with a high correlation to GDP growth). For this reason, the slope of the curve of payments in a volume linked payment will be higher. Theoretically, for the same volume of revenues, payments in the first years will be lower and payments in later years will be higher (that is, the payment profile is “back ended”). However, due to this back-ended nature (higher average life of the total amount of payments), financing is naturally amortized later. Therefore, the overall financial burden is higher. In addition, volume risk is usually more likely to create a penalty in terms of premium, so equity the IRR, DSCR, and interest rates are likely be somewhat higher. As such, all of them usually result in a higher total volume of payments in NPV terms.

|

The following are the most relevant features of this type of mechanism, so structuring decisions should focus on them.

Volume risk structuring

In shadow tariff or shadow toll projects, the final structuring or refinement of the structure will usually be focused on delineating and limiting the volume risk. Where demand may be volatile or suffer material changes in the course of the project (which is typically the case in transport projects), it is not uncommon to establish a system of bands to share part of the risk and reward. For traffic or volumes below certain thresholds, the shadow fare will increase so as to compensate for part of the loss of revenue due to the lower traffic volumes. Conversely, the tariff will decrease if the traffic volume is above certain bands, that is, it is in excess of the baseline curve of the traffic forecast.

The bands or any other method used to temper the traffic or volume risk should be carefully assessed to avoid entirely protecting the private partner from the risk. This would harm the VfM and affect the rationale of the entire PPP contract.

In some projects, the payments are not capped and governments have faced unexpectedly large payments as a result. This creates undesirable, open-ended fiscal risks for government. Regardless of whether a band system is in place, there should be a maximum traffic level above which government makes no payments.

However, where traffic is above the maximum traffic threshold, the contract should compensate the private partner for the risk related to extraordinary levels of traffic (above the traffic limit set out for payments) because they will face to higher O&M costs and likely increased or accelerated renewals. Such compensation can be achieved, for example, by defining a small shadow tariff as an approximation of the marginal O&M costs, or by establishing a right to negotiate compensation if traffic is permanently above the maximum traffic threshold.

Shadow tolls, usually with bands, have been very common in countries such as Portugal and Spain[22] in the early stages of the development of their PPP frameworks. However, from the early 2010s, all projects in Spain have made use of availability payments, and in Portugal some projects have been restructured to implant the availability approach. The UK also initially used shadow tolls for road projects before moving to models based primarily on availability and measures of traffic congestion.

Indexation of shadow tariffs

The other basic factor in delineating the final form of the shadow payment mechanism is indexation. The most common approach to indexation is again to link the payment to the CPI[23] or other suitable price/cost inflation indicator (sectoral index).

The rationale of this is obvious: to link the inflation of the price of the service to that of the general economy or relevant sector. It also has the advantage of increasing the payments over time, which may be desirable if the government wishes to increase the affordability of the payments in the early years of the PPP.

In some projects, a fixed indexation factor (for example, 2 percent) is applied regardless of the actual CPI level for each year. The rationale for such an approach is doubtful, as the government will finally pay the price/cost of transferring inflation risk to the private partner. In turn, the private partner will either charge a premium on the equity IRR requested or enter into a hedge against inflation risk (for example, an inflation swap).

Some projects consider an indexation formula (polynomic) based on different price indexes for different cost factors. While this may be appropriate for very specific projects and circumstances, simplicity is the recommended general approach.

Regarding the CPI, the index is usually the national or general CPI for a particular economy. However, some sub-sovereign procuring authorities use their regional or state CPI. This can be appropriate as long as the cost inflation for the specific project correlates better with the domestic (local or regional) economy than with the national economy. This is frequently not the case.

Performance correction

As explained in the introduction to payment mechanisms (see chapter 1.4), volume-linked payments are not inherently linked to performance requirements. However, the contract may provide that a breach of established performance levels will result in the private partner being required to pay a penalty or liquidated damage (LDs) to the government. In this sense, the structure of volume-linked payment mechanisms is independent from the ultimate design of the performance requirements and target levels of service.

However, as in an availability payment mechanism (discussed in section 4.10 below), rather than imposing monetary penalties on the basis of each individual breach of requirement, some systems include a “quality component”. This fixes the deduction in two stages, based on the number of performance points accrued and then calculating the deduction as a function of these (see box 5.32 “Performance Point Systems and Persistent Breaches”).

Shadow payments work well as a complementary payment mechanism (that is, to supplement user revenues in unfeasible user-pays PPPs) when the feasibility gap has not been filled with capital grants or other forms of financial support. In these cases, the supplementary public payments often include availability or quality elements. These decrease the volume risk of the project.

[22] For a review of the Spanish experience in shadow toll PPP roads, see La Experiencia Española en carreteras (Andrés Rebollo, 2009) commissioned by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) in http://publications.iadb.org/handle/11319/4890, where annex 2 provides for a case study of a PPP based in shadow toll bands.

[23] Also referred to as Retail Price Index, RPI.

Add a comment