The first stage of project identification is the identification of a public need[2]. Projects are not an end in themselves. They are enablers for the government to meet its service delivery obligations. Hence, the government needs to understand what the problem is that it is trying to solve before it starts identifying possible projects. Possible problems might be a lack of transportation links within the country, or a low quality of health service. Having identified the problem, the government can then identify what is needed to solve that problem. For many needs, an infrastructure project is part of the solution.

There are two broad ways in which a government can respond to identified needs.

1. The government can respond to an individual need by identifying an individual project. The overall project may have one or more infrastructure components that should be tested for PPP suitability.

2. The government can respond to a related group of needs by developing a comprehensive plan that identifies a range of proposed projects. The plan may be for a single sector or across a range of sectors, and it may be for a single geographical area or for the entire country. See box 3.4.

The list of identified projects, responding to individual needs or forming part of a plan, is called a pipeline. It is also important that the connectedness of projects is not overlooked. The effectiveness of one project might be increased significantly if another project is also undertaken. Awareness of such connections should be taken into consideration in a plan and should have an impact on how projects are evaluated.

|

BOX 3.4: Example of a Plan – Master Plan for Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia Economic Development 2011–2025 The plan should be based on a long-term agenda for economic development. It must factor in the strategic infrastructure investments that should be funded to make the economic vision achievable. The most effective master plans will have clear targets for improvement in all relevant sectors and will have been crafted with input from all the crucial constituencies, including citizens and business leaders. Several countries have employed this systematic approach. The Indonesian government, for example, has developed a pipeline of infrastructure projects based on its Master Plan for Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia Economic Development 2011–2025. The blueprint outlines how Indonesia will transform into an advanced economy over a period of 15 years, and it calls for developing six “economic corridors” — regions that focus on specific industries. Investment projects are then developed based on the type of infrastructure, such as roads or ports that would be needed to support those industries. |

A pipeline is important to attract investors, because investors prefer to invest in a market that has a recognizable pipeline rather than a small number of isolated projects. A government's project pipeline should contain all of its major projects, regardless of procurement method. All other factors (for example, risk, return, and so on) being equal, the presence of a pipeline is attractive because it suggests a structured approach is being followed and that there is a genuine intention to invest in the future prosperity of a wider market segment rather than just an isolated project. Another good reason for having a pipeline is to enable an investor to see the potential to invest across a spread of projects in the same market segment, where they can also benefit from lessons learned and a similar contextual background. Moreover, a consistent approach to determining the appropriate procurement method will give the market the comfort that a sufficient number of PPPs are likely to be forthcoming, which in turn makes the market more attractive, attracting robust competition.

After identifying the project, it is necessary to clarify the scope and definition and any other related, specific information. This includes a description of the main aspects of the project and related matters such as the physical condition of the site. For further details see section 2.6.

A project’s economic soundness and its alignment and consistency with the public sector’s strategic objectives are paramount factors before deciding to move forward with a technical alternative. Any project selected should be tested for economic feasibility regardless of the procurement route/method (PPP or traditional). Therefore, another benefit of a plan is the fact that projects in the plan have usually already been selected on the basis of their economic feasibility.

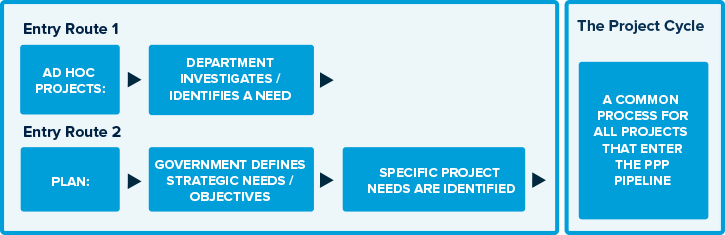

Figure 3.2 summarizes the more informal way (ad hoc projects) and a more formal one (plan/program) as alternative entry routes to a project pipeline.

FIGURE 3.2: Entry Routes to the Pipeline

When a potential project comes from a plan, it will be moved directly to assessment, with the first task being a CBA analysis to confirm that the project solution selected (the project identified) has Value for Money to the society in socio-economic terms. A CBA might already have been done at the time of the definition of the project for inclusion in the plan. When this is the case, the CBA may need to be re-assessed depending on the level of confidence and work done at the time of the plan definition.

An alternative way to feed the pipeline, as described in chapter 2.6.6, is through unsolicited proposals. According to the Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF) from the World Bank[3], there are various motivations for a government to pursue infrastructure projects through unsolicited proposals. Regardless of these motivations, an unsolicited proposal will have to fit with strategic objectives or respond to a clear need already identified by the public sector and have to be included in the project list or the plan. The challenge that unsolicited proposals bring is that they should not bypass the system. Instead, if the government wishes to consider unsolicited proposals, it should make them part of the system.

“(...) mechanisms have been developed to encourage unsolicited bids while also ensuring that competitive tendering is used when identifying the best investor. These mechanisms involve a careful review of such unsolicited proposals to ensure they are complete, viable, strategic, and desirable” [4]

[2] We are assuming that the need is already identified in a previous stage.

[3] Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF). Unsolicited Proposals – An Exception to Public Initiation of Infrastructure PPPs: An Analysis of Global Trends and Lessons Learned (2014)

[4] Hodges, J., Dellacha, G. Unsolicited Infrastructure Proposal: How Some Countries Introduce Competition and Transparency (2007), Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF)

Add a comment