The complexity of the procuring authority’s PPP project requires the consortium to adopt a project management approach to ensure that all necessary experts and skills are managed in an effective and timely manner. Upon signing the Letter of Intent (LOI), Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), or Consortium Agreement (CA), and certainly no later than receipt of the RFP, the consortium will ensure that a bid manager is appointed. The bid manager will be responsible for the following tasks:

- Managing the bid submission process on behalf of the consortium.

- Leading and coordinating the preparation of successive RFP responses, if required.

- Leading and managing the completion of key tasks, such as due diligence activities, and commercial and financial feasibility reviews.

- Defining the work program, key tasks, interfaces, critical paths, and milestones that need to be completed to ensure the consortium’s RFP is submitted on time.

- Identifying the necessary resources needed to complete the RFP response, such as in-house resources, external advisers, logistics, and so on.

- Preparing the RFP proposal’s budget: direct and indirect costs, and contributions from sponsors.

- Drafting proposals for the project sponsors steering committee to approve. These will be key decisions about the approach to take and positions to adopt in the RFP response.

- Dealing with the procuring authority’s representative or third parties as and when required.

Typically during the initial stages of responding to the RFP, senior staff from one of the sponsors will assume the bid manager’s function on a temporary basis until a permanent appointment is put in place. Likewise, one of the sponsors may provide personnel from its organization to work as part of the bidding team preparing the RFP.

For large and complex PPP projects that have been identified through the sponsors’ due diligence, and which are strategic targets for them, it is likely that a bid manager will be put in place before a PPP project has been officially launched. The role of this bid manager will be to monitor the development of the target PPP project for two reasons: to identify when it might be launched into the market, and to liaise with the procuring authority in order to build a good working relationship early on.

Carrying out these activities will help sponsors and/or the consortium prepare in advance for the large and complex PPP project. This will be sound commercial practice, as time will be limited once the RFP is launched; any work that can be done beforehand will be useful.

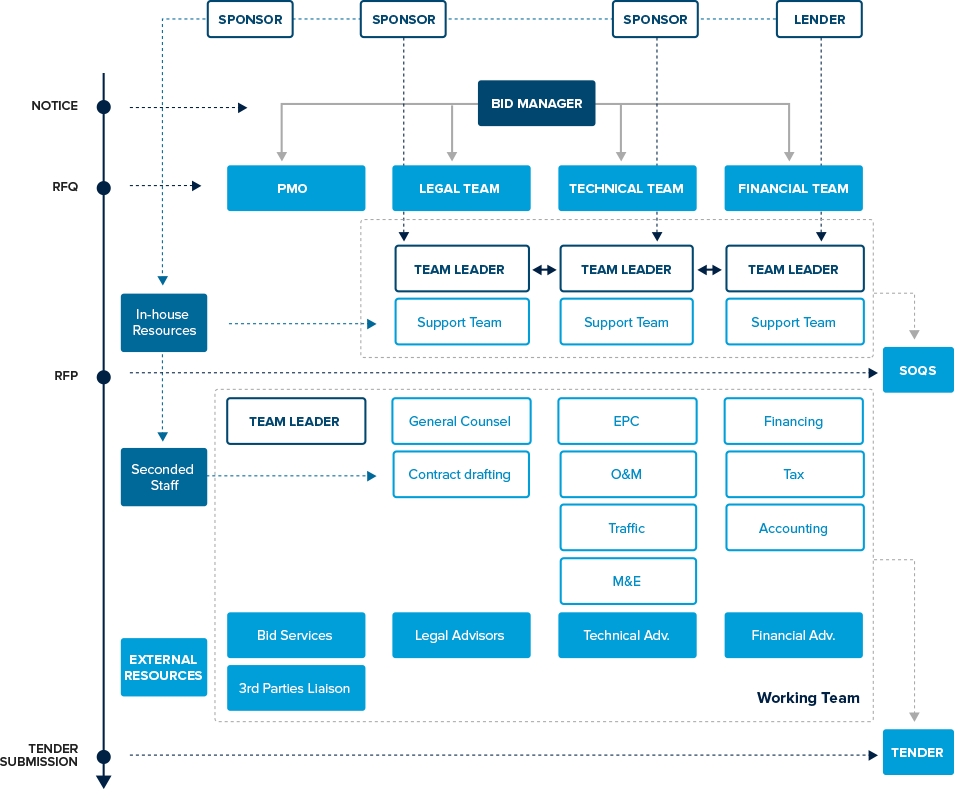

FIGURE 6A.10: Bidding Team Resources over the Tender Process

Note: PMO=Project Management Office; SoQ= Statement of Qualifications.

Once the RFP is released, the bid manager will assume full responsibility for these duties and for the preparation and submission of the RFP response.

As described in figure 6A.10, when preparing the RFP response there are generally three working teams: the legal, technical, and financial teams. Each team will have a team leader and a supporting or working team to provide assistance. In some cases, consortium members may have additional advisers working for each of them. At the beginning of the RFP response preparation, the working teams would normally be made up of internal personnel (the input from external advisers is not very significant at this stage).

As noted, once there is certainty about the tender process and the RFP details, then external resources and advisers are used. These external resources will supplement the existing internal resources provided by the sponsors. Normally when the bidding process is ongoing, there will be key milestones to be met with their associated deliverables, such as the completion of feasibility studies and assessments.

At times, especially when the RFP proposal preparation work becomes significant, seconded personnel from (one or all) of the sponsors may join the bidding team to assist in preparing final or crucial deliverables. However, this practice will only work successfully if the seconded personnel have sufficient time to devote to the preparation of the RFP proposal. Their complete cooperation is needed so that they become fully active members of the different teams working effectively alongside the external advisers.

From the sponsors’ perspective, using seconded staff will help to ensure alignment with the sponsors’ corporate guidelines, although it is recognized that the collective views of the consortium members will need to prevail.

In large and complex projects, a Project Management Office (PMO) may be created in order to assist the bid manager. The PMO is normally in charge of setting standards and targets (and ensuring that they are followed), as well as the gathering and production of information for management review and managing/monitoring the tender milestones and deliverables.

It is useful to highlight that responding to an RFP successfully and submitting a tender response is about implementing sound project management techniques in relation to the tender, such as the following:

- Organizing the tender development process: Defining objectives and organizing the right people.

- Planning the timetable for the development and submission of the tender response, including: identification, assignment, and timing of tasks.

- Managing the execution of the tender submission, that is, motivating/focusing the bidding team, making decisions, allocating scarce resources, and monitoring the process.

- Ensuring consistency and the integration of the complementary aspects of the tender response.

- Learning for future tenders.

Organizing and managing the resources required to submit a bid is a significant exercise and is costly for the sponsors. A proportion of the cost is, therefore, normally included in the final tender price under the heading of “management costs”. Additionally, it may be possible for the procuring authority to meet some of the costs, especially where the PPP project’s procurement has been protracted.

6.7.1 The Technical Solution

Appropriate management of key technical risks and solutions is a major challenge for sponsors. Getting the right technical solution is not, however, an easy task. Construction is a multi-phase and highly complex industry in which the different phases are carried out by different parties. Apart from inherent technical challenges, there is always a high risk of loss of information, lack of coordination, and poor quality of outcomes.

The technical solution will be designed by the technical team, helped by external specialized consultants, such as engineering specialists who will work under the direction of the technical team leader or a technical committee.

In order to arrive at the optimal technical solution, it is necessary to work toward the best design, that is, a design that is functional, sustainable, efficient, and that meets quality standards. Good design adds value. This can only be achieved with the following factors.

- Proper definition of output requirements and quality standards from the procuring authority.

- Having the best technical advisers on board.

- Clear definition of roles/responsibilities within the consortium as well as the main interfaces.

- Proper management of a fully integrated supply chain.

Taking into account the output nature of PPPs, good design should start at the early stages of the tender process. The procuring authority does not normally provide significantly detailed design, technical information, or even technical information that is warranted. In practice, this means that as soon as the tender requirements are well known, the private party must start from scratch in obtaining its own technical information. Despite the fact that some information might be provided by the procuring authority, it is crucial that each private party obtains (directly or indirectly) its own information or set of studies.

In some cases, the procuring authority might provide full PPP project designs or construction requirements. In these circumstances, the private party will not normally assume any risk relating to the accuracy of the provided requirements — unless there is an opportunity to review the final design and to propose design variations and changes of standards.

The main aim of the design process is to define the PPP project scope of work, identify suitable metrics, and assess the costs. The former includes the assessment of RFP technical and quality requirements, the assignment of objectives among the technical team (who is responsible for what), and the development of the conceptual design. The latter includes defining a Design and Construction (D&C) schedule, a Bill of Quantities (BoQs), Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), technical specifications, and a budget/cost for construction (Capex).

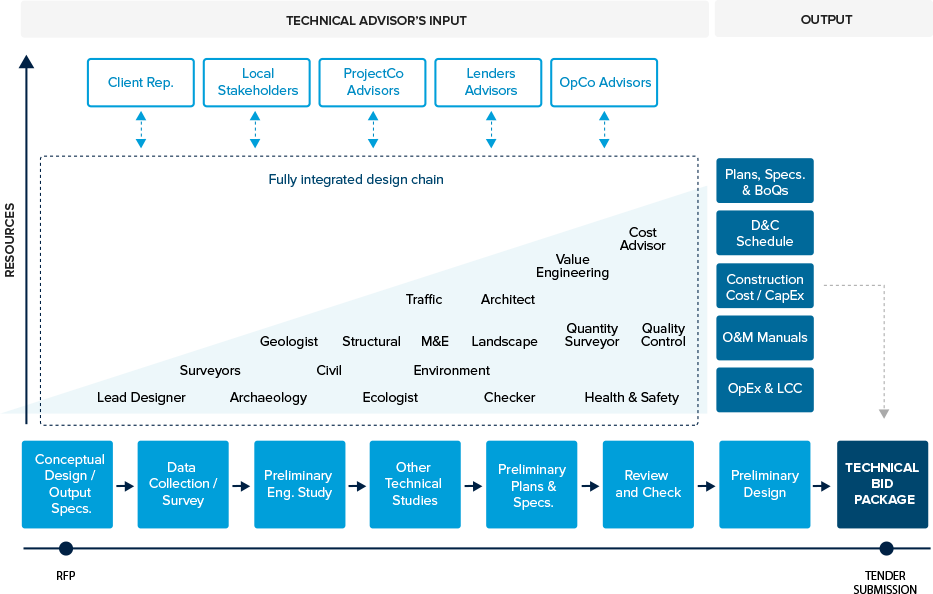

Typically, in a PPP project the technical solution will be developed incrementally as the tender process progresses – see figure 6A.11 below. As such, the procuring authority should allow sufficient time in its procurement timetable to enable this to happen. Where the technical solution is heavily reliant on the use of technology, such as the provision of computers in a school, then it will be necessary to assess the proposed technology and upgrade it as the PPP project develops. Only by doing this will the provision of up-to-date technology be assured. The final and definitive technical solution will normally only be developed once the PPP project is awarded. The sooner the final design is ready (and formally approved by the procuring authority) the sooner the construction will start.

FIGURE 6A.11: Design Process and Interfaces

Note: BoQ= Bill of Quantities; CapEx= capital expenditure; D&C= Design and Construction; LCC= life-cycle costs; OpEx= operational expenditure; O&M= operation and maintenance.

Similarly, in relation to the Operations Phase, the starting position is the RFP’s output-based and performance-based specifications. These will be taken into account in the project’s technical requirements (O&M Manuals). The technical team will produce the long-term O&M plans, as well as an estimate of the operational costs (Opex) and life-cycle costs (LCC) for the PPP project over the duration of the project agreement.

It is well known that higher specifications involve higher construction costs. However, they also lower operational expenditure because maintenance requirements may be less for a PPP project asset with higher specification, as it will normally have a longer life cycle. Conversely, lower construction costs usually result in higher operational costs or larger investments over the life of the asset.

The tension between construction and operational costs means that each of the construction and O&M contractors’ approach to costs may conflict. As such, it will be incumbent on the SC to manage this issue and to agree on an approach. It will be crucial however to ensure that whole-life costs are kept to a minimum without compromising quality and outputs. In doing so, benchmarking, cost targeting, and value engineering methodologies must be used.

As noted, the appointment of an experienced multidisciplinary technical team is important. However, it should be emphasized that proper management, straight-forward communication, and full integration of the supply chain is imperative. Only by putting in place the right rules and procedures will it be possible to save time and money — minimizing the chances for errors, omissions, extra works, and/or litigation.

At the end of the technical process, there will be two main inputs: the technical bid package and the assessments of costs associated with the PPP project (costs adjusted to the risk assumed by each party). Subsequently, these outputs will be taken into account to carry out the necessary financial analyses and to build up the financial model/outputs. It is important to highlight that the final (and binding) decisions with regard to Capex, Opex and LCC will be adopted very close to, or just before, bidding submission. Therefore, the sponsors, steering committee, and the bidding team must be prepared to make fast decisions under very tight schedules.

The technical solution will drive the PPP project, and consequently it will form a key part of the project agreement.

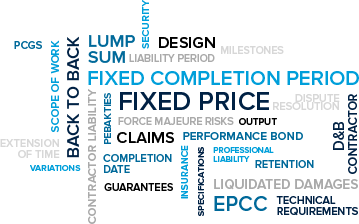

IMAGE 6A.12: Key Design and Construction (D&C) Contractual Drivers

Note: D&B= Design and Build; EPCC= Engineering, Procurement and Construction Consortium; PCG=parent company guarantee.

6.7.2 The Financial Solution

The financial solution comprises the business case used by the private party to approve its decisions to invest in the PPP project and to submit its bid. It will set out the private party’s financial strategy and financial structure (the optimum mix of debt and equity) for the PPP project.

The financial model[7] is one of the tools used by the private party to help it make a financial assessment of the PPP project, and to assist it in structuring its project finance solution.

6.7.2.1 The Financial Model

The most important function carried out by the consortium’s financial team is to develop its financial model. Normally, the financial team will delegate the preparation of it to a financial adviser and this financial adviser will carry out its development under the supervision of the bid manager and/or the financial team leader if there is one. See box 6A.2. The financial model is necessary to help the consortium prepare its bid, as well as provide the procuring authority with a method of assessing the robustness of the consortium’s RFP response.

The financial model will be comprised of a number of separate cost elements which will be combined to form the total price that the private party will require in order to implement the PPP project. In practice, there will be, for example, amounts in the financial model that set out PPP project costs (such as construction, O&M, and financing costs). All of these costs need to be added together in order to calculate the total price offered by the consortium.

In terms of assisting the consortium to prepare its bid, the construction of the financial model serves a number of purposes.

First, it assists in the financial analysis of the PPP project, including the payment mechanism, and it is used to assess the appropriateness of the PPP project as an investment opportunity for the consortium. It does this by identifying the relative project risk-return. A favourable assessment will help inform the decision to submit or not submit an RFP response. Most importantly, it will help determine the price and costs of the elements that make up the private party’s RFP proposal.

For example, the financial team, or the financial advisers if instructed by the financial team leader, will review the PPP project’s payment mechanism and assess predicted project revenues. For “government-pays” projects, the SPV will have made an assumption about the annual unitary charge it needs to receive from the procuring authority in order to deliver the PPP project. Payment to the SPV will, however, be dependent on the delivery of an expected service at an expected level. A failure to deliver this will result in a deduction made against the monthly unitary charge paid by the procuring authority. For instance, in a hospital PPP project, if one of its wards is unclean then it will be deemed to be unavailable and an unavailability deduction will be made.

The financial team will therefore be keen to test how aggressive the proposed PPP project payment mechanism is. This allows them to estimate the likelihood of deductions and the associated effect on the PPP project’s anticipated revenues. It will do this by running scenarios and sensitivities using the financial model.

Similarly, under “user-pays” projects where the SPV receives revenue from the user of the PPP asset, for example road users paying tolls, the consortium’s financial team will be involved in forecasting both use and revenues. These forecasts will be used to assess if the anticipated use made of the PPP asset, plus any constraints on toll levels imposed by the procuring authority, will generate sufficient PPP project revenues. Again the financial model will be used to test the scenarios and help inform decisions about the suitability of the PPP project.

Second, the financial model is used as an aid to help the consortium assess certain parts of its RFP response, as well as helping it to assess the overall value and appropriateness of its proposal. For example, the financial model will be used to help determine the fixed construction and O&M prices which are key parts of the overall proposal submitted to the procuring authority. It does this by enabling the consortium to test a variety of prices until it gets to an optimal total price for the PPP project.

Third, the financial model is used to test financial structures and so help determine the type of PPP project financing to be used by the consortium. For example, the funders will specify a set range of sensitivities they want the financial advisers to assess using the financial model. The financial model will therefore run test scenarios, such as assuming a debt- or bond-financed project.

It will also be able to test the impact of different debt terms or strategies (for example, using a short-term or mini-term loan which is then refinanced after construction) on the equity IRR. The benefit of being able to test different scenarios is that it will reveal the advantages and disadvantages of each approach. It will also help in the assessment of the degree of risk attached to the proposed funding. Thus, the financial model will help the consortium decide which funding solution to adopt.

The financial model will also be used to test proposals and counter proposals that are considered during the procurement negotiations. The ability to run sensitivities will also help with the consortium’s negotiations with potential funders. The consortium will be able to input the funder’s requirements into the financial model to see what effect such requirements will have on its anticipated project return. Where the effects are less favourable to the consortium, it will be able to highlight this to a prospective lender by using the financial model. As such, the financial model becomes a tool used by the consortium to help it negotiate funding terms with its funders.

The financial model is a key component of a project and reflects the financial basis upon which the PPP project has been agreed. It will be submitted to the procuring authority as part of the response to the RFP. It provides a robust assessment of the consortium’s costs and revenues inherent in its RFP response. It is the information in the financial model that determines the amount of the annual/ monthly payment that the SPV will need to receive in order to meet all its cost liabilities. As a consequence, it will be fundamental for the procuring authority’s financial advisers to fully understand the information contained in it.

The consortium’s financial model is a computer model showing a detailed analysis of the anticipated income and expenditure of the PPP project, its cash flow and balance sheet projections, together with any reserves and contingencies required. It will also include details of the assumptions underpinning the monies set out in the financial model.

The financial model is a necessary component of the consortium’s RFP response documentation. It will enable the procuring authority to carry out a robust assessment of the consortium’s costs and revenues. It also enables the procuring authority to compare how each private party bidding for the PPP project has structured its financing, as well as the financing assumptions the private party has made (for example, regarding interest rates or inflation).

When each private party’s financial models are reviewed as part of the competitive bidding process, it will reveal the genuine differences between parties. It will also reveal how sensitive the RFP responses are to external factors, such as interest rate changes. In order to ensure consistency when making comparisons between parties’ bids, the procuring authority will make certain assumptions regarding, for example, rates of interest and exchange rates such that it will assume the rates are the same for each party’s bid.

While the financial model is produced by the consortium as part of its response to the RFP, it will continue to be adjusted to reflect the financial consequences of any PPP project changes agreed with the procuring authority during the bidding process and throughout the term of the PPP project.

|

BOX 6A.2: Financial Advisers’ Activities

|

6.7.2.2 Funders to the PPP Project and the Types of Funds they Provide

The financial structure of a PPP project, as in any project financing, requires the provision of debt and equity. Debt and equity can be provided by a number of entities, and they are normally provided at the point where the consortium changes its status and incorporates into the SPV. It should be noted too that the capital markets can be used to raise debt funding.

The sponsors will inject equity into the PPP project by becoming shareholders in the SPV. They will have an equity stake in the SPV. Additionally, they may provide subordinated debt, especially if this ensures a favourable treatment for taxation purposes. International and domestic commercial banks will be the usual funders to the PPP project unless a project bond structure is developed (see below). Multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, through the International Finance Company (IFC), the European Investment Bank (EIB), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the African Development Bank (AfDB), and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) may also provide a source of project finance. Export credit agencies can also be a funding source.

Other potential debt providers are debt funds, sovereign wealth funds, and pension funds. Such providers may provide equity.[8] The optimal mix of funding sources will be dependent on their availability for a particular PPP project in a specific market, as well as the overall cost of funding for the PPP project. See box 6A.3.

|

BOX 6A.3: Examples of Entities that may Act as Project Funders

|

The main features of the debt and equity elements of a PPP project’s financial structure are set out below.

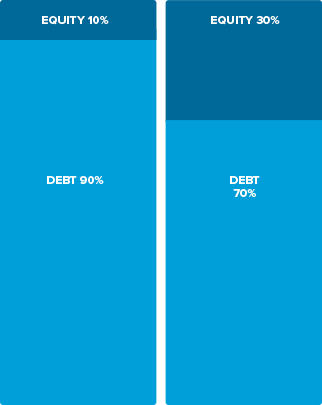

Debt

Most PPP projects receive debt financing from banks. Debt financing is normally the cheapest form of project finance. Bank financing normally results in a bank lending, for example, 70–90 percent of the monies required to fund the PPP project, with the balance of 10–30 percent coming from equity providers. The amount of debt provided to a PPP project as a percentage of its total funding requirement is known as its gearing. In respect of the above examples the gearing is 90–70 percent, and the split of debt and equity sources of finance is represented by the ratio 90:10/80:20/70:30 respectively. It should be noted that a PPP project’s gearing depends on the risks attached to the specific PPP project, with certain project sectors receiving a lower proportion of the debt than others. See figure 6A.13.

FIGURE 6A.13: Capital Structures: Equity/Debt

The cost or price of debt is normally the underlying cost of funds to the funder plus its margin and the associated fees. The margin is the additional funder’s costs to cover the risk of the SPV’s loan default and the costs of putting in place the loan itself.

The underlying cost of funds is determined on the basis of floating/fluctuating interest rates. The cost of lending money over 20–30 years, the typical length of a PPP project, will not remain constant. However, the PPP project cash flows will generally be constant. This means that there is a mismatch between the constant/steady state revenues that the SPV receives under the PPP project — and the ever changing interest rates that apply to the underlying costs of funds borrowed.

This issue is addressed by the SPV taking out a financial product to pay a fixed amount of interest for the funds borrowed. This financial product is known as an interest rate swap and it will be purchased at financial close.

Debt repayment

Debt is repaid over the lifetime of a PPP project. The debt payment profile will be set out in the funding agreements and will be determined at financial close. Normally, debt will be fully paid off before the PPP project term ends, leaving a period of time when all monies coming into the PPP project will be paid out to the equity providers.

Funding contingencies

It is not unusual, although it is undesirable, for a PPP project to face unforeseen financial liabilities such as cost overruns. When this happens, funds need to be found to make payment. The monies required are known as contingency funding. The amount of contingency funding will be set out in the financial model.

Currency for borrowing

Although there is no correct practice, borrowed funds will normally be in the local currency used to make payment to the SPV. Should the local currency be particularly volatile, then the procuring authority may find that the SPV will charge a higher cost of funding because of the increased risk of the PPP project revenues being devalued.

The currency of capital outlays and the availability of funds from local markets will also affect the cost of funding. The procuring authority, in a “government-pays” project, may therefore find it beneficial to make payment in US dollars or pounds sterling. These currencies are stable and payment in them will be attractive to the SPV because it will help mitigate its currency risk.

Equity

Different types of investors can provide equity. These include infrastructure funds, third party investors, and construction and O&M companies. Equity is injected through the acquisition of share capital by individual shareholders. When equity is provided, the equity provider will acquire shares in the SPV and be classified as a shareholder.

Payment of equity, known as a dividend, normally occurs after the PPP project’s debt (including subordinated debt[9]) has been paid, so it happens late in a PPP project’s term. This means that it is most at risk. Should there be insufficient PPP project revenues generated because of poor performance of a PPP project, then it may not get paid out. As it is most at risk, and its payment is deferred, the equity providers will expect a much higher return for the monies they have lent. It is more expensive than debt.

Use of the capital markets

Bond financing of PPP projects is not the prevailing source of finance. However, it provides an alternative funding instrument that the SPV can access through the capital markets. Specifically, it provides long-term finance for the PPP project which can complement the debt provided by the funders. However, bonds are less flexible than bank debt.

The process of carrying out a bond issue varies from country to country. If a bond is going to be issued, then it will be necessary to obtain local financial and legal advice so that a robust commercial, financial, and legal due diligence can be carried out on the project and the procurement process.

For any bond issue, it is a prerequisite that there be an appropriate risk allocation between the PPP project parties. Additionally, each of the PPP project parties must have a strong covenant that is supported by different types of security. In practice, this means that the approach to these issues, as evidenced above in the case of a debt financing, is broadly similar.

There are a number of stages that a bond issue goes through and these can be summarized as follows.

- Pre-launch – deciding the type of bonds to issue, their value and terms.

- Road show – marketing the prospective bond launch so as to attract investors who will buy the bonds.

- Bond issue – issue of bonds to investors and the payment of funds.

Bond issues can take a short or a long period of time to put in place. It will depend on the country where the bonds are being launched and the project sector, as some sectors are more attractive than others.

6.7.3 The Legal Solution: Review and Drafting of Legal Documentation

The consortium’s legal team will be made up of internal and external legal advisers. It will have a number of tasks to complete.

Some tasks will need to be completed as part of the PPP project screening process. Activities required at this stage include carrying out an assessment of the key legal requirements that are already established (for example, it may be known early on that there is a requirement for the SPV to have the procuring authority as a shareholder), and reviewing the legal impact of the allocation of PPP project risks.

Other tasks will be completed as part of the bid preparation process. The legal team will have to work with the consortium’s commercial, technical, and financial teams to ensure that their different solutions that form part of the RFP proposal can have legal effect. This means that there will need to be a review and assessment of the legal issues arising out of the project agreement, and the consortium will need to be advised of the conclusions.

The legal team will also have a role in considering the legal aspects of the procuring authority’s funding requirements. For example, the procuring authority may request that the PPP project is bond financed, and in this situation the legal team would advise on the financial, regulatory, and legal compliance requirements.

It may be possible to amend the project agreement (if this is permissible it will be stated on the PPP project tender documentation), and if so then this is a task that the legal team will carry out at this stage.

The legal team may also be required to carry out legal due diligence to assess the legal powers of the procuring authority to carry out the PPP project procurement. It may also carry out due diligence on the legal and regulatory framework of the PPP project.

As part of the bid preparation process, the legal team will need to put together the package of legal documents required for the RFP response. There are different practices worldwide. Some countries require that all the key PPP project contracts are drafted, agreed, and submitted as part of the legal package. This would include the construction and O&M contracts, the agreements that create the SPV, and in some cases the funding documents.

Other countries do not require such a detailed response and accept heads of terms (a summary of the key terms to be included in the contracts – see below) for each of the key contracts at the point when the RFP response is submitted. When this happens, however, the legal team will be required to draft and agree to all the key contracts at a later time during the period from the appointment of the preferred bidder to financial close.

Some legal tasks will be ongoing ones and will be carried out throughout the PPP project procurement. Such tasks include negotiating with the procuring authority, the funders, and the consortium’s supply chain contractors.

In summary, the legal team will have the following key tasks.

1. To review the legal aspects of the RFP, including the project agreement, to interact with the procuring authority and to prepare the package of legal documents that form part of the consortium’s RFP response.

2. To prepare the agreements necessary to set up the SPV (its constitutional documents); draft the heads of terms for the construction and O&M contracts; and draft, negotiate, and finalize the construction and O&M contracts.

3. To review the funders’ finance documents and draft the associated legal documents, to participate in the general commercial negotiations, and to support the fundraising negotiations.

1. Reviewing the legal aspects of the RFP, interacting with the procuring authority, and preparing the package of legal documents that are a requirement of the RFP

The legal documents issued as part of the procuring authority’s RFP will include the project agreement, the direct agreement, details of the required insurances, and the bid bond and required security. On occasion, the procuring authority may provide or specify the forms of security it requires to provide an assurance that the SPV will deliver the PPP project as required. For example, the procuring authority may require a Parent Company Guarantee from the construction contractor that will guarantee the proper performance of the construction works.

The consortium’s legal team will consider the legal documentation provided by the procuring authority. The team will highlight the key obligations and responsibilities the procuring authority requires the SPV to assume.

The legal team, together with the consortium’s advisers, will also advise on the risk allocation inherent in the legal documentation and its acceptability. Using this information, the consortium will be able to make an assessment of the obligations and risks that can and cannot be accepted.

During the course of the PPP project procurement and/or during the bid submission period, the consortium will, through its legal advisers, let the procuring authority know its view of the terms of the legal documents. It will do this in writing, at meetings, or through a combination of both throughout the bidding process.

The key terms within the procuring authority’s provided documentation that the legal advisers consider can be found in table 6A.1.

TABLE 6A.1: Key terms within the legal documents provided by the Authority

|

Project Agreement SPV’s obligations and responsibilities Construction matters O&M issues Payment and financial matters The effect of changes in law Force majeure, delay events and relief events Termination, including event of SPV or authority default Sub-contracting arrangements Dispute resolution procedure |

Authority Direct Agreement Step-in rights |

Insurance Required insurances, including Construction All Risks, Business Interruption, Advance Loss of Profits, Third Party Liability, and general project-specific insurances.

|

Bid Bond and Security Quantum of bond Bond duration On demand nature Scope of the parent company guarantee |

Note: O&M= operation and maintenance; SPV= special purpose vehicle.

The legal team will be responsible for checking that all the RFP requirements are met, and that the consortium’s RFP response is compliant.

2. Preparing the agreements necessary to set up the SPV (its constitutional documents); drafting the heads of terms for the construction and O&M contracts; and drafting, negotiating, and finalizing the construction and O&M contracts

The key legal agreements that need to be prepared are as follows.

v SPV constitutional documents

The consortium’s legal advisers will spend a significant amount of time establishing the SPV, for which the following is required.

SPV formation checklist

- Identify the SPV’s name.

- Identify the SPV’s address.

- Specify the number, name, and address of directors.

- Specify the names and addresses of the shareholders.

- Determine the size of each shareholder’s share allocation, including the share types and value.

- Enter into a memorandum of association, that is, an agreement to form the SPV.

- Agree to the rules that govern how the SPV will operate (the articles of association).

- Prepare a statement of capital.

- Draft and agree on the shareholders’ agreement.

In most cases, the formation of the SPV does not require the involvement of the procuring authority. There may, on rare occasions however, be a requirement for the procuring authority to be a shareholder in the SPV. It will also be prudent for the procuring authority to carry out checks in some key areas. For example, some procuring authorities require the SPV to be incorporated in the country where the PPP project will be carried out; and some also apply restrictions on the age and qualifications of those who can be appointed as SPV directors.

v Shareholders’ agreement

One of the key tasks for the consortium’s legal team will be to draft the shareholders’ agreement. As noted, the shareholders will be the project sponsors. The shareholders’ agreement needs to address, among other things, the following key issues in table 6A.2.

|

SPV Board Representation and Voting Issues |

Composition of the SPV board; number of directors and their voting rights; inclusion of a chair of the SPV board (or not); format of board meetings; decision-making and how to deal with deadlock between directors and disputes. |

|

SPV Governance |

Regularity of meetings; approach to conflict of interests. |

|

Budgeting and Dividend Distribution Policy |

Developing and implementing the SPV’s annual financial plan; implementing the dividend distributions policy, and developing and approving changes to it. |

|

Selling Shares and Shareholder Exit Process |

Development of shareholders’ rights to purchase shares before any other party has the opportunity to purchase them (pre-emption rights); the timing and the process to be adopted for shareholder exit, and the scope of the indemnities to be provided to the remaining shareholders. |

|

SPV’s Daily Activities and Management |

Identification of the work the SPV will carry out; its method of working; and its operational management structure. |

v Heads of terms

The consortium’s legal team will initially assist in the preparation of heads of terms (HOTs) for the construction and O&M contracts which are entered into between the consortium and the construction and O&M contractors. Although not binding, the HOTs will set out, in summary, the key commercial areas that the consortium and the construction and O&M contractors expect to be included in their contracts. Specifically, they will set out the degree of acceptance that can be given to the project agreement obligations that will then need to be passed through to the contractors. The HOTs will be developed throughout the bidding process, and will eventually form the basis of the construction and O&M contracts that will also be prepared by the legal advisers.

v Construction and O&M contracts

The construction contract may be based on international standard forms, such as those promoted by the International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC). If so, then the consortium’s legal team will amend the standard form to ensure that it contains a full pass through of the construction obligations contained in the project agreement. It will also include additional requirements that the SPV will expect its contractors to comply with (for example, the requirement to provide a performance bond for completion of the construction work). These additional requirements will sit alongside the typical contractual requirements found in such contracts, such as the requirements for a fixed construction price, a fixed completion date, and the payment of milestone payments on completion of fixed packages of construction works.

If a bespoke construction contract is used, such as a “design and build” (D&B), instead of an international standard form, then the consortium’s legal advisers will draft it so that it will mirror the form and content of the project agreement. It will also contain a direct pass through of its obligations (see below). In addition, it will reflect the commercial agreement between parties regarding price, lump sum payment, milestones, and the construction completion process.

Unlike construction contracts, O&M contracts are not based on standard forms and so will be bespoke in nature according to the procuring authority’s PPP project. In this respect, the drafting of the O&M contract will be carried out in a similar way to the drafting of a bespoke construction contract. The O&M contract will mirror the form and content of the project agreement, and will contain a pass through of the project agreement’s obligations to the O&M contractor. The O&M contract will contain additional commercial terms, such as a yearly price with a formula for inflating it on a yearly basis and life-cycle obligations.

The construction and O&M contracts written by the consortium’s legal team will contain a number of key terms, as outlined in boxes 6A.4 and 6A.5.

|

BOX 6A.4: Key Sections in the Construction Contract

|

|

BOX 6A.5: Key Sections in the O&M Contract

|

Pass through of obligations and risks

The consortium’s legal team will ensure that there is a direct pass through of the project agreement obligations into the construction and O&M contracts. In practice, this means that the consortium’s legal advisers will ensure that each of the construction and O&M obligations contained in the project agreement are extracted and used to form the basis of the construction and O&M contracts, respectively. Typically, in terms of documentation this might look like the following example in box 6A.6.

|

BOX 6A.6: Pass through of PPP Project Obligations Project agreement term – construction “The SPV shall complete all the construction works necessary to provide the PPP facility.” Construction contract term ‘”The construction contractor shall construct the PPP facility for a fixed sum.” Project agreement term – O&M “The SPV shall provide the procuring authority with the O&M services.” O&M contract term “Following completion of the construction of the PPP facility, the O&M contractor shall provide the O&M services to the SPV in accordance with the terms of this O&M contract.” |

The approach to the pass through of the project agreement’s risks is illustrated as follows in table 6A.3.

|

Project Agreement Risk/Obligation |

Pass Through Treatment |

|

SPV responsible for cost overruns and construction delay

|

Risks of price and time to be borne by the construction contractor through the construction contract requiring construction works to be completed for a pre-agreed fixed lump sum and by the completion date prescribed in the project agreement. |

|

Performance and service deductions

|

Poor performance deductions under the project agreement recovered by the SPV through the operation of the construction and O&M contracts. These provide for the contractors to compensate the SPV and make payment to it for poor performance. Liability of contractors to the SPV will be capped however, and shortfalls will need to be met by insurance or SPV’s reserves. |

|

Construction defects

|

Construction contractor liable to meet the cost of remedying defects by assuming liability under the construction contract. |

|

Life cycle

|

The O&M contractor is liable under the O&M contract to meet the cost of ongoing maintenance and life cycle. Receives regular payments from the SPV managed life-cycle fund to carry these out. Failure to carry out life cycle and maintenance may result in monies being withheld. |

|

Termination and replacement of sub-contractors

|

Poorly performing sub-contractors can be terminated and replaced by the SPV. The construction and O&M contracts provide for the SPV to be compensated if a replacement sub-contractor is required. |

|

Land acquisition/planning and other consents

|

May be retained by the procuring authority. Alternatively, may be retained by the SPV or be the responsibility of the construction contractor under the construction contract. Where retained by the procuring authority or the SPV, the construction works will not normally commence until the land and consents are acquired. |

|

Site and soil conditions

|

Risk is passed to the construction contractor under the construction contract. |

|

Environmental matters

|

Risk is passed to the construction contractor under the construction contract, and to the O&M contractor under the O&M contract. |

|

Strikes and protester action |

Risk is passed to the construction and O&M contractors under their contracts. |

|

Change in Law

|

Risk is retained by the procuring authority where it is discriminatory or project specific. Risk of general changes of law is passed through to the construction and O&M contractors under their contracts. |

The consortium’s legal team will also need to consider and advise on the interface issues that exist between the contractors. An example of such an issue is delay. Should the construction program be delayed, then the O&M period will normally be reduced because of the effect of the fixed PPP project term that means the operational period cannot be extended by the length of the construction delay. A shorter O&M period means that there will be less revenue available for the O&M contractor. The O&M contractor, as it is not responsible for the construction delay, will wish to ensure that it receives compensation from the construction contractor to cover its loss. However, the O&M contractor has no direct contractual right to sue the construction contractor for this loss. There is therefore the need to create a direct contractual relationship between the O&M contractor and the construction contractor. This is done through an interface agreement. It is the interface agreement that creates the contractual rights between the contractors, and it gives each a right to sue and be compensated by the other, should this be required.

3. Reviewing the funders’ finance documents, drafting the associated legal documents, participating in the general commercial project negotiations, and supporting the fundraising negotiations

PPP projects necessitate the completion of a significant amount of funding documentation. The consortium’s legal team will work closely with its financial team to ensure that the funding agreements are negotiated robustly with the lending institutions, and that they accurately reflect the agreement reached between the parties. As with all of the contractual documents, the legal team will work with the sponsors to ensure that the terms and conditions of the funding documents are acceptable.

[7] In practice, the private party may use two financial models: one which is provided to the procuring authority to support the calculation of its tender costs, and another which contains the ‘true’ cost of the private party’s bid and which is for internal use only.

[8] In some countries, the equity providers may be allowed to transfer their shares early on (for example, before the construction works start). In such a case, it is not uncommon for sponsors to pre-agree with an investor on the disposal and transfer of a percentage of their equity shares to the investor. This means that the equity investor would become an equity participant in the PPP project at the same time as financial close. In other countries, however, all equity investors will have to be part of the bidding consortium from the beginning in order to be allowed to invest in equity. If this is not the case, then the investor will only be able to become an equity investor after the construction works are completed.

[9] The benefit of subordinated debt is that it can be repaid throughout the term of the project at an agreed fixed rate of interest and provides the sponsors an additional return.

Add a comment